A virus that infects all other areas of thinking

What was it that made Crow so contagious an image? Among the ways we might run with that question, I want to suggest here that what we meet staring back at us from Crow’s ponderous, guilty face may include a burgeoning sense of unease, or dislocation, that the writer Timothy Morton, some 40 years later, has spoken of as ‘the ecological thought’.

Far from a conscious preoccupation with ‘going green’, Morton’s ecological thought concerns the all-pervasive entanglement of our immediate experience within a slippery, centre-less ‘mesh’ – a strangely ungraspable web of relations wherein both other beings, and our own queasily interconnected fields of experience, only get weirder, more deeply haunted by a sense of otherness, the longer we look at them.

So the ecological thought, for Morton, isn’t really a ‘position’ that we might choose to accept or reject. Its something more autonomous than that, more devious, even – a thing acting upon us already, like a strand of DNA code. Like a virus, as Morton puts it, infecting all other systems of thinking, feeling and behaviour, altering them from within, gradually depleting the incompatible ones.

A verb that’s sometimes used to talk about what illustration does is to illuminate, as in to shed light on. As a way of talking about image-making, it’s a word closely associated with religion, of course, with traditions of the sacred. So what might it look like for a drawing to illuminate this creeping infection within our inherited notions of the human, and of that sacred animal’s place within what so many now to refer to, following the writer David Abram’s lead, as a ‘more-than-human world’? And what sort of light, in particular, might such an illustration shed on the curious blank spot that grows, like an unthinkable numbness, on the other side of poor environmentalism’s must do better?

With these preoccupations on the table, then, I’d like to look back to Hughes’ and Baskin’s collaboration – to see what their Crow, and his afterbirth Cave Birds, might have to say about all this. So here’s an 11-minute clip from The Artist and the Poet, the film-maker and photographer Noel Chanan’s 1983 recording of Baskin and Hughes discussing the evolution of this work.

A magical operation

Crow and Cave Birds form the core of a 15-year creative friendship between Baskin and Hughes, begun when both were well-established in their respective fields. And, as Baskin puts it, their two streams of work were already ‘crow-haunted’ when they met. Baskin, who seeded the idea for Crow, speaks of their relationship as ‘not one of influence, but of presence’. Of Crow’s presence, we might say, within both men’s lives – their friendship a matter of reciprocal recognition, as each found the face of their abject-exultant familiar mirrored in the work of the other. It was this sort of mutual recognition, perhaps, that sustained the 15-year imaginal dialogue between them – a conversation that flowed both through and about practice, and which operated, as we’ll see, on several levels at once.

And here, then, is our first layer of hidden agenda: that ‘magical operation’ that Hughes observes, swimming through their work at an invisible level. Hughes is being playful perhaps, but his pleasure is palpable as he shares his discovery, years after the fact, of a prophetic element within their collaboration, hiding in plain sight in both words, and pictures – a strikingly precise foreshadowing of Baskin’s soon-to-be diagnosed brain tumour, and of the subsequent operation to remove it.

And there’s a shared sense of confirmation, it seems, in that discovery. But, a confirmation of what? Whatever the nature of this elusive enchantment, one thing we can say about it is that it went about its quiet business, unobserved, as the two men focused their attention on developing the work’s main themes, on honing its constituent parts. We can also note that, for Hughes at any rate, this kind of autonomous, invisible agency within poetry was no less than an article of faith, and a creative touchstone: that any genuine collaboration between artists, for instance, happens ‘at this hidden, telepathic level – or not at all’.

An underswell of divination

Which brings us to a second unspoken presence within Baskin’s Crow, and to – as he puts it – the voluntary ‘iron fetters’ against which their work pressed. Hughes comments in The Hanged Man and the Dragonfly, his introduction to Baskin’s graphic oeuvre, on his friend’s famously derisive criticality – on Baskin’s insistence, in both art and life, on the tangible, the real, and his abhorrence for anything within art which he saw as departing from that real. And real, for Baskin, meant the weight of ‘our common suffering’, for which – as with his great mentor, William Blake – the only ‘whole and adequate symbol’ was the human form. But, unlike Mr Blake’s, Hughes observes the human form that we encounter in Baskin’s work to be in a highly permeable state of flux, enduring constant incursions by other entities, and undergoing a prolonged, unstable mutation.

And braced against Baskin’s wide-awake, sceptical gaze, Hughes’ essay goes on to observe a pressure, mounting as what he calls ‘a biological weight of necessity’ within that parade of monsters. Hughes imagines its unspoken, insistent presence as ‘an underswell of divination’. Not exactly religious, perhaps, although we’re in that territory. ‘Something’, Hughes speculates, ‘that survives in the afterglow of collapsed religion’. All of that ‘inward learned Jewishness’ in which the Rabbinically-trained Baskin was saturated, ‘busy dreaming for him’, below his conscious radar, ‘in a rigorous, divining fashion’. And this hidden religious life that The Hanged Man and the Dragonfly proposes as the kernel of his friend’s graphic work, is revealed, Hughes suggests, not so much in the mythic vocabulary which it adopts, as in the mark which transmits all of those cumbersome, zoomorphic angels to the page.

The scratch-marks of an arcane calligraphy

And here, then, is the fundamental constraint framing this collaborative work. One shared, for all their marked differences, by both artists, as they trained their gaze on form, language, poetic resonance. Hughes’ prose writings show how his lifelong interest in the numinous and the supernatural was grounded, at all times, in a close attention to the possibilities of language – to the dangling etymological roots, the emergent rhythms, the incantatory power of words. Likewise, in The Hanged Man and the Dragonfly, Hughes suggests that it is first and foremost in Baskin’s line that we encounter the central character of his work – his graphic line ‘an image in itself – his fundamental image’. The scratch-marks of an arcane calligraphy, as Hughes puts it, ‘improvised from the knotted sigils and clavicles used for conjuring spirits’. And that charge of secretive spiritual exultation coursing along Baskin’s graphic line, most fully personified, earthed, in those mutating raptors he could never quite get away from, who kept precipitating from its presence ‘as crystals out of a supersaturated solution…solid and sharp with the salts and metals of it’, to be absorbed through the eye and into the nervous system of the viewer, where ‘they dissolve back into the real knowledge and presence of it’.

As between poet and the illustrator, then, so between between line and image, between image and word, and between reader, and both: a relationship of presence.

A hole in the fabric of our understanding

If Timothy Morton’s playful entanglement of the ongoing conversations between art and ecology does offer a good line of approach to this work, I think Crow returns the favour, with interest. ‘The current ecological disaster’, Morton tells us, ‘has torn a giant hole in the fabric of our understanding’. Or rather, it hasn’t. It might be nearer the mark to say that ecological collapse has revealed the gaping hole underlying the dominant culture’s relentless, instrumentalist logic – or as my friend Christos Galanis might put that, the hole beneath its aberrant, in-animist worldview.

If there’s a hole here, its surely one that – throughout our species’ lethal 12,000-year swerve off its slow track through deep time – has been here all along. And the crucial role of art in negotiating this leaky territory right under our civilised feet may turn out to have less to do with Green message-dissemination (however urgent, or desperate the cause) than it does with art holding open a space within that dying way of life which is used to accommodating intensity, shame, abjection, loss; used to welcoming persistent imaginal others to the table, familiar visitors who give tongue to whatever grieving, intractable dilemmas civilised humans find themselves unable or unwilling to speak within their brightly-lit, death-phobic culture.

As the warnings of impending disaster get more shrill by the day, Crow’s quizzical stare points out, perhaps, that – as Morton puts it – the disaster’s already happened, so ‘it’s important not to panic, and strange to say, overreact to the tear in the real. If it’s always been there, it’s not so bad, is it?’ Maybe that’s what we can hear in Crow’s unkillable laughter, as he spraddles about inside that hole, looking for stuff to eat. A curious thought, that nothing ecological crisis might throw at us could exceed the sheer, feathered strangeness of our own embodied, animal natures.

Sources

Hughes, Ted & Baskin, Leonard, Cave Birds: An Alchemical Cave Drama Ted Hughes & Leonard Baskin, Faber and Faber, 1975

Hughes, Ted, Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow, Ted Hughes, Faber and Faber, 1970

Hughes, Ted, ‘The Hanged Man and the Dragonfly’, from Winter Pollen: Occasional Prose, Faber and Faber, 1995

Morton, Timothy, The Ecological Thought, Harvard University Press, 2010

The Artist and the Poet, Noel Chanan’s 2009 DVD of his 1983 audio recording of Hughes and Baskin, accompanied by the author’s photographic essay. Copies of The Artist and the Poet are available here: tedhughes.online

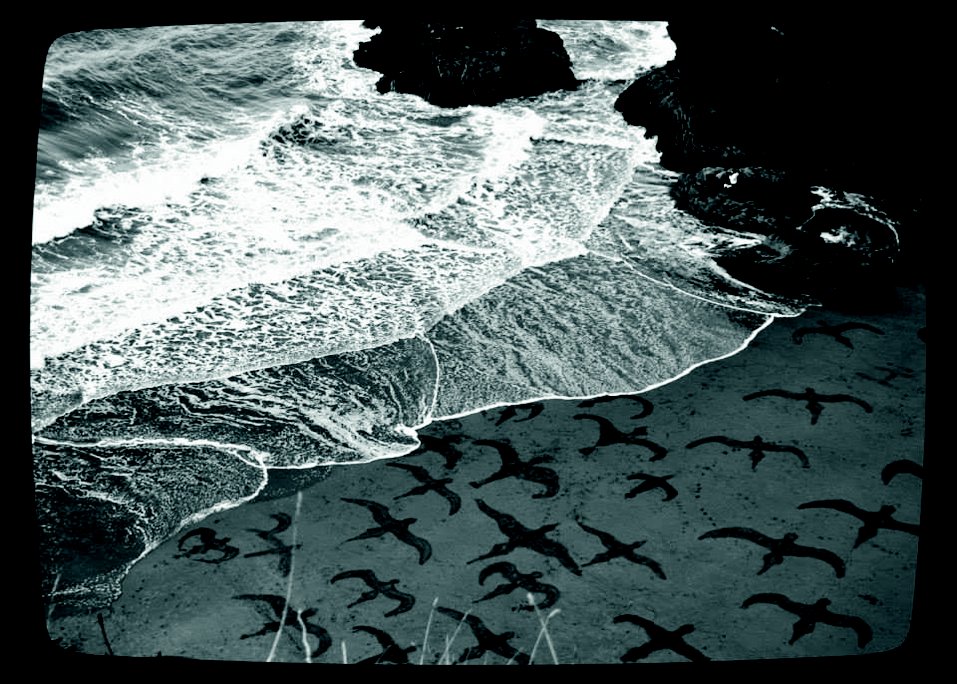

Images